Animal Crossing: New Horizons' museum is one of the crowning jewels of the game, serving as both a monument to your achievements and a serene space to hang out with your friends. And as it's International Museum Day today, what better time to geek out about what a lovely place Blathers' pride and joy is?

But what makes it such a great addition to your island? And, in the midst of a global quarantine, how does it succeed (and fail) in making us feel like we're actually in a real, working museum? We sought out an expert to help us understand where Blathers has gone right and wrong on his path to making Animal Crossing's museum such a memorable place.

So many bones.

© Nintendo

Natalie Kane is a curator of digital design at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (though she is currently on furlough as all of the city's museums are shut down due to the coronavirus). The V&A has previously hosted exhibitions including Design/Play/Disrupt which, among other evolutions in gaming technology, featured an Enviro-bear 2000 arcade cabinet. As the person tasked with helping visitors understand the evolution of software and computer interface design, Kane is obviously interested by Animal Crossing's replication of her daily toil, despite this being her first experience outside Pocket Camp.

It's quite a difficult time for museums at the moment, as their sole purpose is to allow as many of the public as possible to come and learn about the world. But when visitors are put at risk by indoor gatherings, education can't trump public health. In an interview on BBC radio, Director of the V&A Tristram Hunt suggested that the museum – one of a handful in London's South Kensington museum quarter known as Albertopolis – is losing around £1 million a month from the nationwide shutdown, the result of 105,115 scones a year currently going unsold at the cafeteria.

Much of this revenue comes from the gift shop and café, two things conspicuously missing from Blathers' new build which has prompted a few more alarm bells to ring in Kane's head as we potter around Animal Crossing's museum over Skype.

"There's no museum staff! It's a really obvious thing but I'm very used to there being visitor experience people, they're the people who make our museums really good," she says. "They are the human contact of the museum, they make it feel less eerie and the [Animal Crossing] museum does feel kind of eerie when you're on your own. But then work is a weird thing in Animal Crossing, no-one works. Apart from Tom Nook and his– are they his children?"

The lack of staff is compounded by very few educational plaques to explain the exhibits, outside of what Blathers himself can tell you when you donate a piece. Since our joint wander around the exhibits, the museum has expanded to include an art gallery which features more informative notes, suggesting Blathers has also realized he couldn't be the sole source of knowledge in the building. And today's Museum Day event adds even more interactivity to the exhibits, reducing the weird void of a total lack of employees.

Visitors can be seen in the museum but no staff other than poor Blathers.

© Nintendo

However work isn't the only thing that seems not to exist within the joyful, but simplified, world of Animal Crossing. Disability as a concept is present only inconsistently throughout the island. Wheelchairs can drop from balloons but exist only as props, and this approach carries through to some of the museum's design.

"These are the things I think about when I walk into any space, it's become a weird second sense whenever I go into museum buildings, is how accessible is this, because it's something you become hyperaware of the need for these days," Kane says. "The lack of museum benches for people with chronic illnesses and chronic disabilities, the invisible illnesses that you don't see. There's definitely a lack of museum benches. It's the only thing. In terms of thoroughfare, though, it's pretty easy. I'd say it's quite spacious."

Benches aren't just for the benefit of those who physically need them, either. The recently added art gallery on the upper floor contains a much more healthy number of seating arrangements, which benefits all villagers, even the ones who just come in to look at their phones.

"If you think about the way buildings and architecture can be quite exclusionary, museums are supposed to be spaces that are quite open and available to people, because they're free a lot of the time," Kane says. "They're places where people meet and they're often places where there's no obligation to participate beyond learning, some people just come inside to eat their lunch."

The aquarium is well spaced out for accessibility.

© Nintendo

And despite a few areas of the museum being impassable to less abled visitors (the aquarium is the only area with liberal ramp usage) in other respects it is quite accessible. "For a wheelchair you want to have about a 120cm turning circle, between two people at an exhibit," Kane explains, guesstimating the size of her villager to measure a gap in the aquarium. "So between the goldfish tank and the wall there should be about 120cm between those. That's a good width for two people to pass each other, or a person in a wheelchair to turn around. Good museum ergonomics."

Of course, good museum design comes down to far more than just whether you can walk around it without getting sore feet. Museums are full of knowledge, and history, and objects, and stories, and without something to help you make sense of all of that you might as well have walked into a junkyard.

"Good exhibition design is supposed to lead you, but the best way you can do that is through narrative, and through lighting and color. It's not often just a big arrow on the floor," Kane says. "You want things to be simple enough that you don't need a map to guide you, but interesting enough that you don't get bored. That you don't think you're seeing the same thing over and over again. You want your eye to be led to something that pulls you into the next place, and actually this exhibition design is quite interesting."

The tree of life leads you through the fossil exhibits.

© Nintendo

The clearest instance of a narrative in Blathers' museum is the tree of life, or genealogy, on the floor of the fossils section. Taking you from the start – the key invertebrate-vertebrate schism in early life – all the way through to the branching off of mammals from our reptilian monster ancestors. In the back room, each villager silhouette is linked to its prehistoric cousins, with an interactive spotlight for you to stand in linking humans to the neanderthal Australopithecus.

"The most interesting is obviously the fossil room because that's the one that has quite clear markers on the floor, but it also has things like a light that draws you into the next room, there's very clear signage on the wall that draws you through," Kane remarks. "But also the upper levels, the exhibits are less important that you follow that narrative. Because you know that you're getting fish, while in the fossil room it's more important that you follow that narrative. Because nearly everything is about the evolution of those things."

However even to form these sorts of narratives starts before the design of the museum, with the institute's collection strategy; how they decide what objects to keep. For Blathers this is something of a simple remit: collect one of every specimen you can find on this island. However even that becomes a more complex ask when you consider how he decides what to keep. If, like us, by now you're handing over four fossils a day and being told that he can't add them to his personal collection, you may be getting a little exasperated at dear old Blathers. And in some respects he's right to limit himself, but Kane isn't sure keeping the first specimen that comes along is a legitimate strategy.

Uncanny resemblance.

© Nintendo

"For someone like the Natural History Museum, or the V&A or Science Museum, why you collect is often to serve the public good in terms of education," Kane explains. "Everything has to be justified in that respect, so it's not a vanity project to collect a dinosaur. Every decision that's made has to be made in order for it to serve the public good. Which is why you end up not having 16 T-Rexes in that sense, because you have to choose one and choose it wisely, and carefully, and for it to be one that is the most communicative or educational in that particular way, or it's particularly significant or it has a particular story attached to it."

If you've ever seen a Brontosaurus in a museum, there's a good chance you were actually looking at a lie. For one thing, the skull of the Brontosaurus has never been found. Most fossil skeletons are capped with hypothetical sculpted skulls or, until recently, the closely related Apatosaurus ajax. Since the early 20th century, there has been strong contention in the paleontology community over whether the Brontosaurus even exists, or is actually the result of forgery by unscrupulous fossil hunters during a gold rush known as The Bone Wars in the late 1800s.

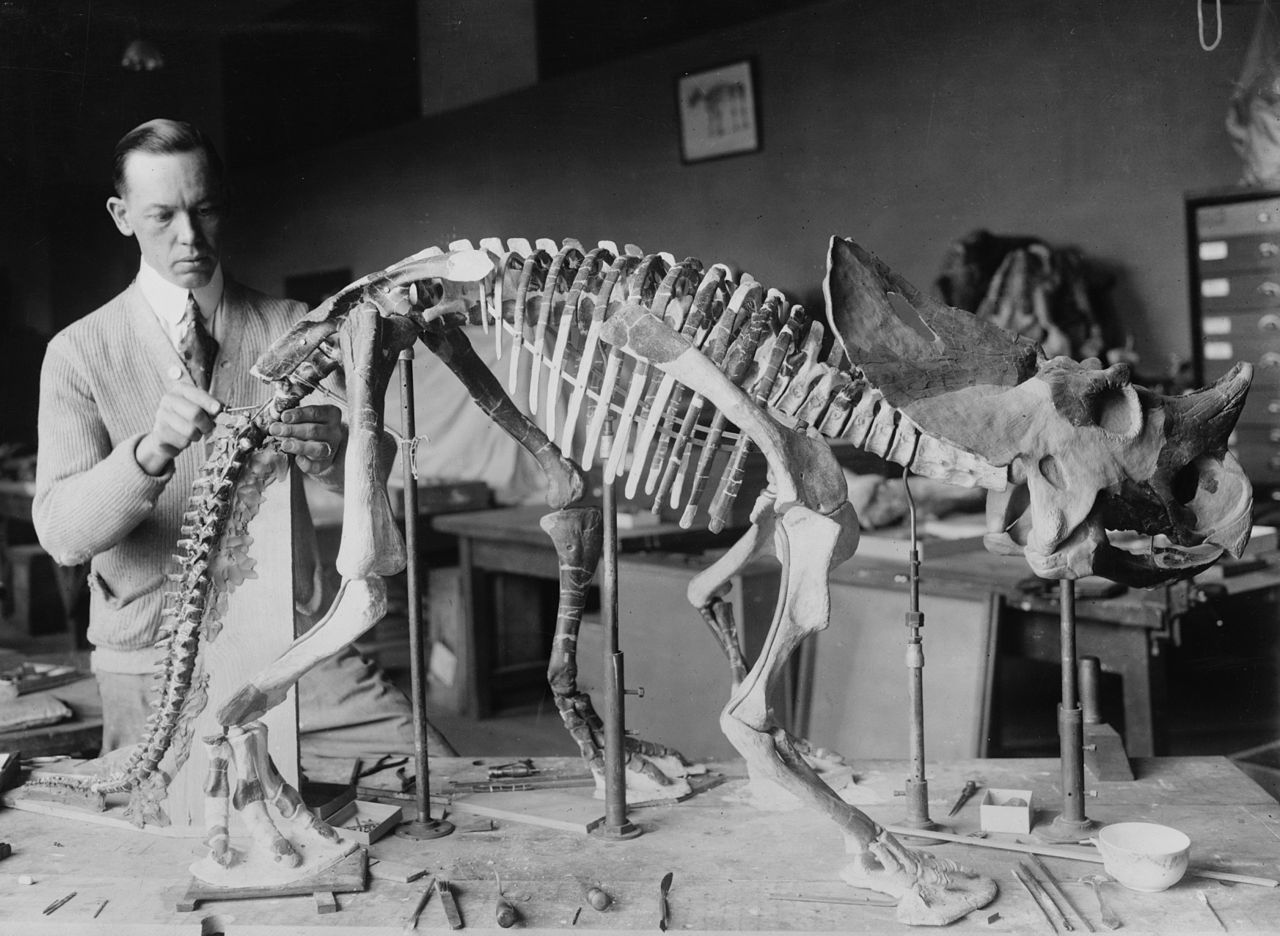

Norman Ross preparing the skeleton of a baby Brachyceratops for exhibition in 1921.

US Library of Congress, cph.3c27774

Nevertheless, despite its unscientific origins, many museums kept their dodgy dinos on display and even retained its Brontosaurus name, long after colleagues suggested it was actually a closely related cousin. They have since been proven retroactively correct to do so, as further research revealed in 2015 that there were just enough differences in their skeletons to make Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus separate genera.

This isn't uncommon, despite the fact the dinosaurs are long since dead we are constantly updating our knowledge of them. One of the fossils currently in Blathers' museum is already out of date according to research released just after the game's launch. But even before the Brontosaurus' eventual reinstatement as a real dinosaur, the fossils were worthy of display according to Kane, precisely because of their imperfect past.

The animal crossing spinosaurus skeleton is already inaccurate and I find that really funny pic.twitter.com/nq1ZkTM1MI

— Ryan Frields (@Reikkusu) April 29, 2020

"They decided to keep that particular skeleton, in certain museums, of that Brontosaurus because of the stories it told of that particular moment in history," Kane says. "They didn't just throw it out, because it was important and encapsulating of that entire story. But you have to make sure you choose, it's not enough to collect one of each, which is what I find quite interesting about the Animal Crossing museum.

"There are some museums that are very completionist, I think in terms of having one of every single thing, while some museums may have different collection strategies. Not every museum is trying to collect every type of design of chair, because you only have so much space and capacity and resources to do that. You have to be quite careful about things like storage, or of how much you can put on display or what is the most communicative story you can tell to your visitor."

As museums are intended as educational spaces, first and foremost, it's no surprise that Kane is excited by the prospect of what Animal Crossing's could do, especially at a time when her own museum is sadly out of commission. Some institutes, such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium, have even attempted to use Animal Crossing as a distance learning tool throughout the coronavirus lockdown.

"Everyone's a little exhausted by every museum going digital and online, but there's something nice about a game being a little bit delightful and interesting as well," she says. "And if you also learn something cool about dinosaurs in the process, that's pretty cool. Like when I play through Civilization V, I accidentally learn about Catherine The Great, Empress of Russia, that I didn't know about. She sounds pretty murderous and badass, that kind of thing.

"This could be a really interesting little learning resource for things like fossils and specimens, especially the rarer or weirder ones that people didn't know about," Kane says. "I know quite a few people who play this with their kids and, especially during this time where a lot of people are home-schooling, it would be really nice if people were able to use this as a secondary resource for that kind of thing."

You can find Natalie Kane on Twitter, or hopefully sometime soon, back at the Victoria & Albert Museum in South Kensington, London. If you've enjoyed Blathers' museum, either as an educational tool or just a calming place to go on a date, then let us know about it in the comments. Happy International Museum Day!